The Commissioner steps to the podium, “The Seattle Seahawks are on the clock with the 26th pick in the first round.” Your heart races. Thousands of hours of film review, discussion, self-scouting, and strategic planning have prepared you for this moment. Twenty-five players are no longer available, but plenty of great ones still are, including a tight end who you never expected to be there this late. You do not have a real need at that position. This guy has All-Pro potential, but might not even play much this year if you take him. There are other players you like who could address an immediate need, but they are less of a sure bet than the tight end. Best player or biggest need? Who do you choose? This is an age-old debate in NFL front offices and among fans. John Schneider and the Seahawks have a demonstrated and discussed their philosophy on this question. The results have been uneven.

The role of team need in player selection

Every team factors need into their draft evaluations. Nobody should suggest otherwise. Schneider has been more direct in explaining that not only does need play a role in their draft decisions, but it impacts the grade they give a player. James Carpenter was a pick that was universally panned as soon as it was made. Even Carpenter’s college head coach, Nick Saban, admitted he was surprised Carpenter had gone in the first round. Was it because Schneider and the Seahawks thought they saw a first-round talent where nobody else did? Not exactly.

“We grade for our team. We don’t grade for the league. We grade for what our team looks like. What ends up happening, you just have specific positions that are pushed, if you will. Like the year we took (James Carpenter), everybody thought we took Carp too high. Well, we had a specific need, so that’s why he was moved up. That’s the way we’ve done it over the years. We have the same process, we grade the same way, our grading scale is the same, but we’re always looking towards the future in terms of, how do we address who’s coming up as a free agent, who can compete at left guard or who can compete at center or left tackle? Those are the things we focus on instead of saying, ‘OK, this guy’s a first rounder, why is he a first-rounder? Here’s a description of a first rounder.”- John Schneider

If you read the quote above, it is clear that Schneider may have had the same grade for Carpenter’s talent level as everyone else, but that he was upgraded due to a need the team identified. That is what he means when he says, “We grade for our team. We don’t grade for the league.” The Seahawks are not trying to stack rank every player from 1-N in terms of talent, and then working to grab the top talent when their pick is called. They grade talent, and then factor in need and scheme fit to arrive at a blended perspective on the value of that player to the organization.

Drafting more purely for talent

Addressing needs is nothing new. For any GM to say otherwise would be disingenuous. It is a sliding scale, though, where not all general managers treat need the same way. The Patriots, for example, drafted Jimmy Garoppolo in the second round of the 2014 draft. Nobody would say New England needed a quarterback, yet they used a high draft pick on one. Two years later, they used a third round pick on another quarterback (Jacoby Brissett). That only happens because the organization places a lower value on addressing needs, and a higher value on drafting the best player available than a team like the Seahawks do. There is a limit to ignoring need as a factor. Would the Patriots draft a fourth quarterback with a high round pick after already having Brady, Garoppolo, and Brissett in tow? Probably not.

Still, they believe in taking the top talent that comes to them. They are not afraid of creating a surplus at a position. Many have argued the Patriots already had a surplus at that position with just two starting caliber players, but now they might have three. A needs-based GM would look at that and cringe, seeing quality draft picks sitting on the bench. The Patriots likely look at it as a way to accumulate more talent. Consider that Garoppolo was the 62nd pick of the draft in 2014. Many thought the Browns would be willing to trade the 12th overall pick this year to acquire him. It is possible some may have given up even more.

If you could travel back in a time machine to 2014, and trade your late second round pick for a guaranteed top 12 pick three years later, while also guaranteeing yourself two years of service time from a quality backup quarterback who was capable of winning a few games when your starter was out, would you make the trade? I would. It is not clear Schneider would, especially if it meant passing on another player who addressed an immediate need.

Take linebacker Reuben Foster. He was a player who many had as a top-shelf talent in this year’s draft. Peter King confirmed that the 49ers had him rated as the third overall player on their draft board. He fell all the way to #31 with the Seahawks on the clock. The Saints were going to take him at #32, and were already on the phone with him when Seattle finished a trade with San Francisco that allowed the 49ers to get their man. Reports are that Foster was not even a consideration for Seattle, and that makes sense given their need-centric philosophy.

Foster is really a middle linebacker. Bobby Wagner is an All-Pro at that position, and K.J. Wright is a Pro Bowler at linebacker as well. When the team goes to nickel defense, one of their linebackers comes off the field, and only Wagner and Wright remain. Foster would probably either be used as a backup or as a SAM linebacker who only plays 30-40% of the defensive snaps if he was selected by Seattle. Wagner is under contract for three more seasons, and Wright for two. Given the pressing needs the team has at other positions, it is easy to understand why Seattle passed on him.

But what if they did not? And what if Foster is truly a future All-Pro linebacker in the mold of someone like Patrick Willis? He still would start out with limited snaps at linebacker and be utilized on special teams. He might go the way of Kam Chancellor, who spent his rookie year backing up Lawyer Milloy, playing in certain sub-packages, and terrorizing opponents on special teams before becoming a full-time starter the next year. He might wind up being needed his rookie year if Wagner or Wright go down with injury, and give the Seahawks quality depth at a position where they have lacked it for a few years. He might even prove good enough that the team considers switching Wagner and Wright around to make room for Foster so they could get the best three players on the field. Wright is turning 30 in two years and will be an unrestricted free agent. Foster could be primed to take over that spot and give the Seahawks freedom to spend salary cap dollars elsewhere.

A surplus is not a bad thing. Talent finds a way to help, either directly on the field or indirectly through trade.

The role of position strength in player selection

The Seahawks selected Malik McDowell with the 35th pick of the draft this year after trading back three times. Schneider has been quoted as saying that the team would have selected McDowell even if they had been unable to trade down from the 26th spot they started in. That means he would have picked McDowell in front of players like Kevin King, Takkarist McKinley, Cam Robinson, and Ryan Ramczyk. Most fans and media take that to mean Schneider believes McDowell is a better player than those guys. Not quite.

Schneider is not asking himself, “Who is the best player?” when the Seahawks number is called. He is asking, “Which player helps us get the most out of this draft?”

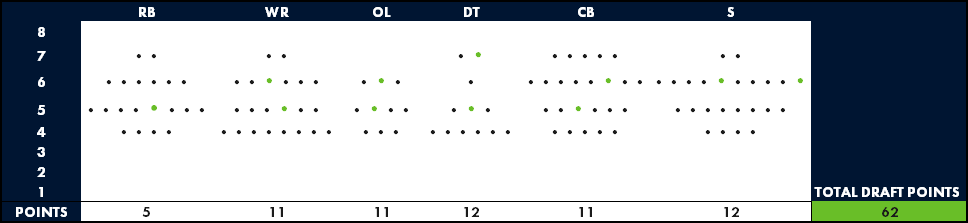

The Seahawks grade every player, and put them into what they refer to as “shelves.” Imagine a player rating scale from 1-8, with 8 being an exceptional prospect who can become an All-Pro, and 1 being not worthy of being in the NFL at all. As a matter of fact, that is a common rating scale for league scouts. There are very few players worthy of being an 8, but 7 and above could be a Pro Bowl impact player, and 6 could be a starter. A very simplistic way of explaining Schneider’s approach would be that he is trying to end up with the highest total number if you added the rating of every player he drafted together.

The graphic above is an attempt to visualize how I believe Schneider sees his draft board. There are a certain number of players that fall into each rating shelf. You can almost put your hands over the player names and just look at how many prospects are available at each shelf. He would probably rank players in each shelf from left-to-right, so there is some sense of who their top player would be at every rating level. When it comes to deciding who to choose, though, his decisions appear based on two primary factors:

- What are the team needs?

- How deep is that position in the draft?

Let’s revisit the King versus McDowell decision. When Seattle was picking at 26, and then again at 31, Schneider was not looking to get the best player from the 7 shelf on his draft board. Even if their was a linebacker who was close to an 8, he would not be considered. He saw a big dropoff at the defensive tackle position after McDowell. He may even have believed there was no other player like McDowell left in the draft. It did not matter whether King was a more highly rated player, who was more likely to be an impact player than McDowell. Schneider would rather exit with the best DT he could grab and a lesser cornerback because he knows he will still get a quality corner later on. Same thing goes for taking Ethan Pocic later in the second round. Pocic may have been the last offensive lineman Schneider thought could impact the team in this draft. He made the same decision in the 2014 draft with Justin Britt in the second round.

“I remember talking to you guys about Justin Britt. We felt like we needed to take Justin right where we did because there was a huge shelf there, a big drop-off.” – John Schneider on the Brock & Salk show last year

This also helps explain why Schneider values quantity of picks over moving up or staying put with higher selections. When it is about total talent drafted, you want as many of the players on your board with the potential to make the roster as possible. That is more important than getting players with the highest upside or the players who are most reliably projected to meet their potential.

The risk with Schneider’s approach

There is a lot of logic to what Schneider is doing. The idea of exiting the draft without any viable interior pass rusher just so he can take a great cornerback instead of a good one sounds pretty crazy on it’s face. Take another look.

The above table is from ESPN, not the Seahawks, but imagine for this discussion that it is accurate ranking of draft prospects by their likelihood to become an impact player. This view of the top draft prospects would indicate that McDowell is the 41st best prospect, where someone like King is the 22nd and Foster is 8th. Said another way, selecting a player like McDowell when higher ranked players are still available means you are passing on a better player and more sure bet in order to make sure a need gets addressed.

That means there is a higher risk your selection does not become an impact player, and it increases the odds that you passed on an impact player. If McDowell becomes Jordan Hill instead of Michael Bennett, while King becomes a reliable starter, the pressure falls to your later picks to work out. The problem is, by their nature as later picks, they are less likely to be great. Shaquill Griffin may become as good, or better, than the corners you could have taken in the first round. That would justify the risk at the top of the draft. History would say it is more likely that a number of the corners taken before him will wind up being better players.

This is where emphasizing team needs and choosing to grab the back half of a deep position in the draft is risky. Schneider looks at a deep position and sees it as a reason to trade back and wait to pick a player from the pool. That approach increases the odds that the team misses out on getting good talent from a deep position. He sees the depth at the position as a chance to get a good player later instead of seeing it as a chance to get a great player early. Five corners were taken before the 31st selection. In a normal year for cornerback depth, King might have been a top 20 pick. The depth created opportunity to get a player who normally would be much farther up the board. The same thing happened with the Seahawks second pick where nine corners were taken before the 58th selection. Some of the corners there would likely have been picked in the early second round in normal years.

Seattle wound up with a corner 32 picks later, who still represents a bargain. He just comes with less certainty, which ironically means you may leave a cornerback-heavy draft without addressing a clear need at the position.

It is a little bit like favoring the buffet to the steak dinner. You get variety and abundance versus the best tasting food. The Seahawks almost certainly exited this draft with more players who have a chance to stick on the roster than if they had decided to stay put at the 26th or 31st slot in the first round. The idea that Schneider got “too cute” and missed the player he really wanted is off-base. He knew exactly what he was doing, and accurately forecast that the guy he wanted would be available all the way down at the 35th pick. He did the same thing with Russell Wilson at the 75th pick a few years back, and that worked out pretty well. It is not that Schneider misjudges player talent. Quite the opposite. He simply places a heavier emphasis on need and total talent drafted than a typical general manager. If Griffin becomes a quality starter, the strategy will be have been worth it. If Griffin does not, McDowell and Pocic will need to be damn good players to warrant missing on a cornerback in a draft chock full of them.