There is evidence that the Seahawks have lost touch with the philosophy that helped them rise to the top. How they confront this identity crisis will have a far greater impact on their football fortunes than any soap opera brewing behind the scenes. In this series, we will explore different aspects of Carroll’s philosophy and assess whether the 2017 Seahawks are in position to recapture their dominant formula.

“If you don’t have a clear view of your philosophy, you will be floundering all over the place. If you win, it will be pure luck.” – Pete Carroll USC Coaching Clinic

[divider]Part Three: Explosive Plays[/divider]

Pete Carroll’s emphasis on creating turnovers is a more well-known aspect of his coaching philosophy, but creating and preventing explosive plays is arguably more important to him. He would never agree with that sentiment, but consider what we learned in the last chapter of this series regarding the drastic reduction in takeaways this defense is creating and how offenses have adapted to throwing shorter passes. If Carroll truly valued takeaways above limiting explosive passes, he would coach his defense to take chances jumping shorter routes, blitz more, and leave the secondary more vulnerable to the deep ball. That is simply not Seattle’s way. Their defense is built, and play called, to take away the deep pass. Their offense is designed to establish the running game so they can set up the deep play-action pass. The Seahawks define explosive plays as a run of 12 yards or more, or a pass of 16 yards or more. Since 2013, they are 41-7 (0.854 winning percentage) when having more explosive plays in a game than their opponent. Unfortunately, that advantage has been dwindling of late.

The Seahawks disappearing explosive advantage

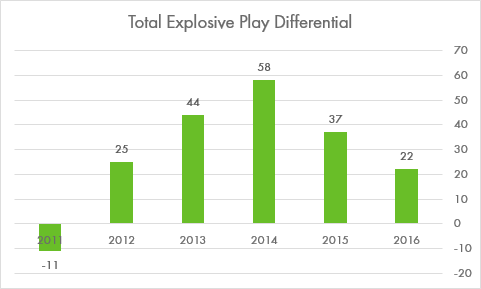

Russell Wilson does many things well, but his greatest strength may be his ability to create explosive plays while limiting turnovers. That is part of what makes him such an ideal fit for a Carroll system. Even when improvising outside of the pocket or the design of the play, Wilson is far more likely to create a big play than a turnover. His addition played a major role in flipping the Seahawks from a negative differential in explosive plays to a strongly positive one.

The team continued to build on that momentum through their two Super Bowl seasons, posting terrific explosive play advantages in both 2013 and 2014. The trend since then has gone the other direction.

Seattle’s +22 advantage in explosive plays was the lowest of the five seasons Wilson has been on the team. Breaking down the cause will give an indication of what the team needs to do about it.

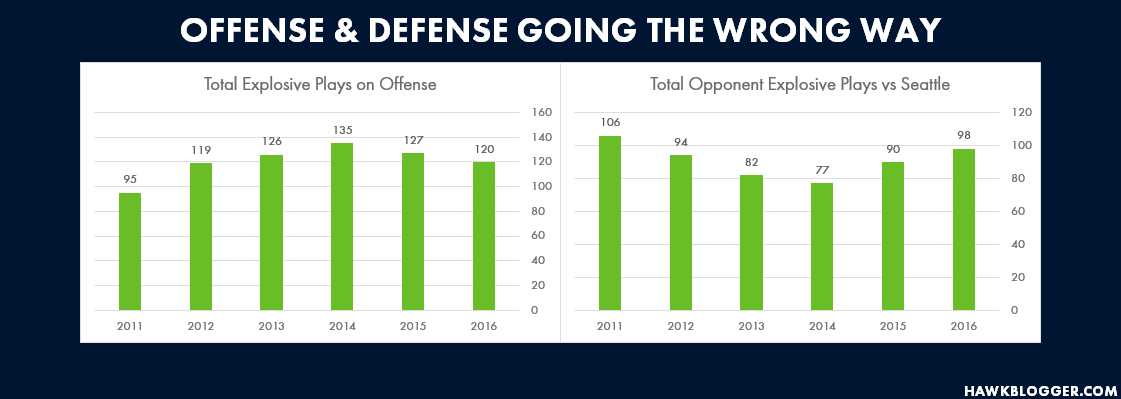

An obvious question is trying to identify if this is more of a problem with the Seahawks offense failing to create explosive plays or the defense surrendering too many. Let’s take a look.

Both the offense and the defense are contributing to the problem. Seattle created 15 more explosive plays on offense in 2014 than they did last season, and are roughly back to where they were during Wilson’s rookie year. The Seahawks defense gave up 21 more explosive plays last season than they did in 2014, and hit their highest level since 2011. Put these both together, and you have a team that is generating one less explosive play per game, and allowing more than one additional explosive play per game than the last Super Bowl team. That is a far harder way to win.

Given the defense has had more of a drop off, let’s take a look to see where those plays are coming from.

Seahawks explosive pass defense in a freefall

The following chart will not be good for your health as a Seahawks fan. Consider yourself warned.

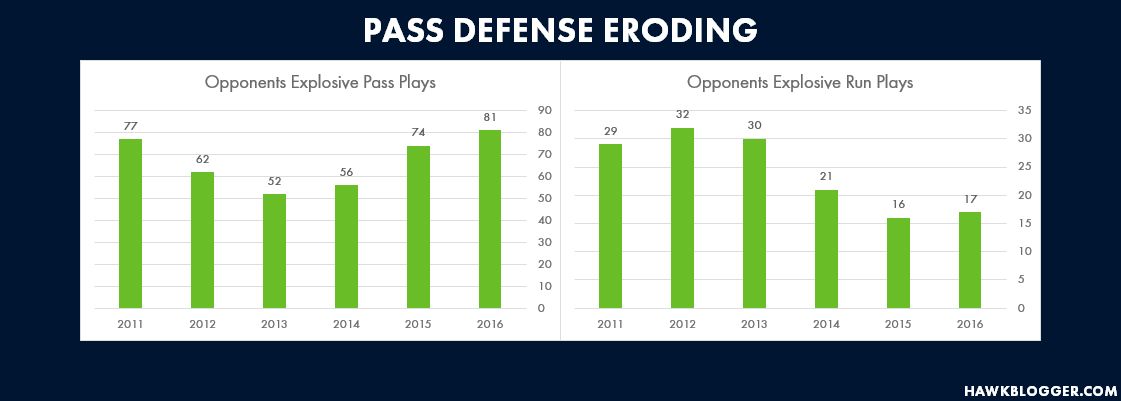

What this shows is the Seahawks run defense has dramatically improved in recent years, and is the best it has been since Carroll came aboard. People remember the terrific pass rush from that 2013 Seahawks defense, but forget that they had some issues against the run. Opponents have managed just one explosive run per game against Seattle the last two seasons, roughly half the rate they were achieving back then. If the run defense is greatly improved, but the overall explosive play total has been increasing, that can only mean…

Seattle’s pass defense is not what it once was. They allowed almost 30 more explosive pass plays last season than they did in 2013, which translates to almost two more explosive pass plays per game. Their total of 81 explosive pass plays allowed was more than Richard Sherman’s rookie season, where he only started about half the year.

Oh, but that is an anomaly because of the Earl Thomas injury, right? I wish.

Opponents averaged more explosive plays per game last year when Thomas was healthy than when he was injured. I know, it makes no sense because we know they attacked more downfield after he was hurt, but I ran the numbers multiple times. The Seahawks yielded an average of 5.3 explosive passes per game when Thomas was healthy, and 4.6 explosive passes per game when he was hurt. They gave up a season-high 10 explosive passes to the Cardinals in Arizona, as well as 8 versus the Patriots, and 7 each versus the Falcons at home and the Rams away. All of those happened with Thomas playing.

Pass defense is often oversimplified to the secondary, but pass rush is a crucial part of any great pass defense. Seattle changed nothing in their secondary from 2012 to 2013, but added Cliff Avril and Michael Bennett and saw their opponents passer ratings plummet (63.4 average rating in 2013, best in the NFL). You can see in the chart above that the Seahawks pass rush became far more lethal in 2013, netting a sack on 7.7% of opponent dropbacks, compared to just 6.0% the year prior. That rate did dip in 2014 and 2015, which likely contributed to part of the explosive pass issues in 2015, but it rebounded last season so it is hard to point the finger at the pass rush as being the chief culprit.

What then? The unsatisfying truth is there is no statistical smoking gun. It would take watching all 81 explosive plays last season and knowing who had coverage responsibilities to form an educated opinion. The players who victimized the Seahawks the most with explosive plays last year:

- J.J. Nelson (5)

- Julio Jones, Kenny Britt (4)

- Julian Edelman, Robert Woods, Brandon Marshall, Larry Fitzgerald (3)

Those are all receivers, as opposed to tight ends. There is a mix of wide receivers and slot receivers. Some of those players we know were guarded by Sherman, some by Jeremy Lane, but many were lined up against DeShawn Shead. Some came against zone coverages where fault is more difficult to pinpoint. Thomas had the most tackles (12) on explosive passes last year. Was that because he was late to a spot or because he was bringing down the guy who beat another defender? Likely both occurred.

What we do know is the Seahawks rise to glory came largely on the back of a ferocious defense, led by a legendary secondary. That advantage appears to be receding, both in interceptions and in explosive plays. The fact that opponents are attacking the Seahawks defense with shorter passes, but managing to pile up more explosive plays through the air is confounding. At least part of the solution has to be better play from their cornerbacks, which is why this year’s draft was so crucial.

The explosive problem on offense

As we saw, defense is only part of the explosive play problem. The offense has dropped off as well. In diagnosing the problem there, we will again separate out explosive passes versus rushes.

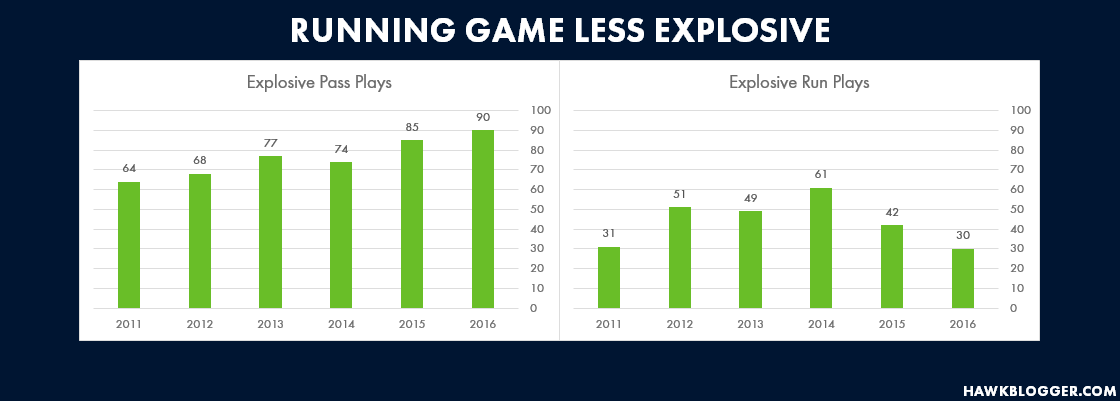

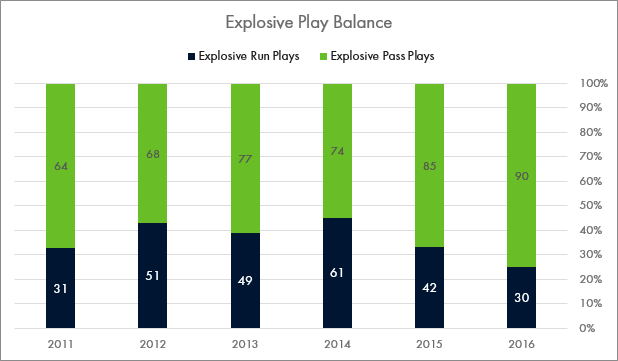

The running game has seen a steady decline in explosive plays while the passing game has been making (apparent) gains. More on the pass game in a moment. Carroll has talked about how important a balanced offense is. We already talked in the last article in this series about how they have lost that balance overall, so it should come as no surprise that the same imbalance is showing up in the explosive play department.

After achieving a nearly 50/50 split in explosive plays across pass and run in 2014, the team last year had the lowest percentage of explosive rushing plays over the past six seasons, and by far the lowest of the Wilson era. This might be acceptable if the passing offense was just becoming overwhelmingly effective and explosive, but that is not the case.

The Seahawks have passed the ball far more over the past couple of seasons, and that increased volume of throws has netted more explosive plays, but the efficiency of that pass offense has not improved. Seattle produced more explosive passes per dropback during the 2013 season (16.6%) than at any other point in Wilson’s career. It is good that we have not seen a significant dropoff, but one would hope an offense with a young quarterback would show some progression. The offensive line play is clearly a big part of the problem. In any event, the charts above show that the offense is just less explosive overall. The running game is significantly less explosive than it was, and the passing game is not improving to make up for the losses in the run game.

Sources of explosive rushing plays

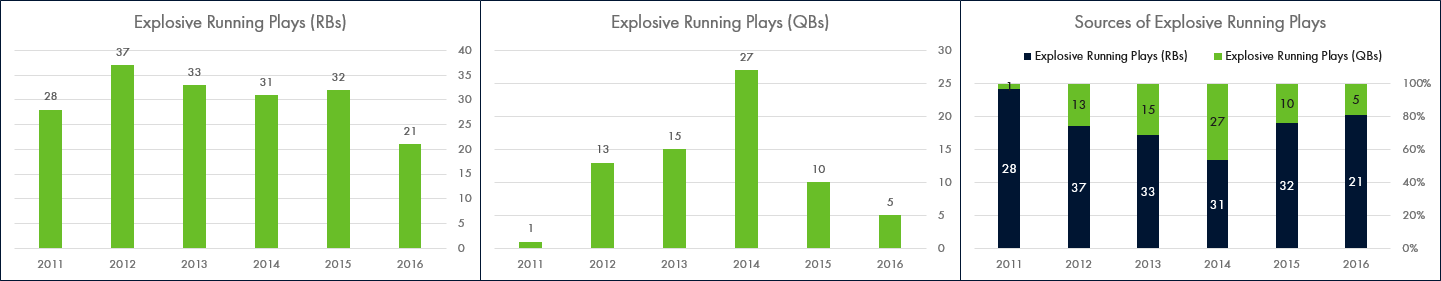

The dip in explosive running plays merits a closer look. I decided to break down where those running plays were coming from to try and ascertain whether this was just a matter of Wilson being hurt last year. The results were illuminating.

There was a massive drop in Wilson’s explosive rushes in 2015, even before his 2016 injury. The 2014 season is an unfair comparison as Wilson had what is almost sure to be a career year running the ball. The 10 explosive rushing plays he recorded in 2015 were below the 13 and 15 he recorded in his first two seasons, but not alarmingly different. We can mostly ignore last year running for Wilson given the myriad of injuries he faced.

What I find more interesting is the drop in explosive running plays from the running backs. Last year saw a precipitous drop in production from that position. That became an even larger problem once Wilson was injured and unable to carry as much of the burden in the running game. Take a look at this one last chart that details the number of explosive rushing plays from the lead running back each year.

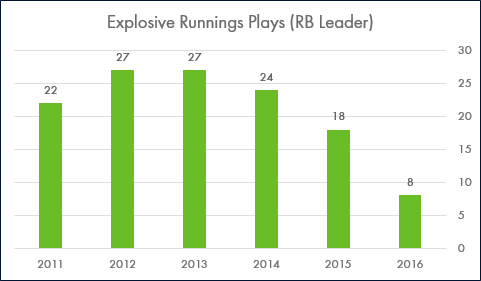

Thomas Rawls led Seahawks running backs with 8 explosive rushes last year. He had 18 the year before. Marshawn Lynch led the Seahawks backs in that stat from 2011 to 2014, and accounted for at least 22 in each season.

This stat, more than perhaps any other, captures the impact of losing Marshawn Lynch to the Seahawks offensive attack

It also explains why the Seahawks have invested so much in that position. The team will have a hard time recapturing their explosive play advantage on offense without a running back who can threaten the defense. Eddie Lacy does not seem to be a particularly explosive runner, but Rawls has been when healthy and C.J. Prosise shows promise as well.

Putting it all together

The Seahawks became the best team in the NFL, in part, by limiting opponent explosive plays and creating plenty of their own. That strength has eroded in the past two years, attributed most directly to a pass defense that is yielding more explosive passes and a running game that is creating fewer explosive rushes.

Wilson’s return to health this year will almost certainly provide a boost to the run game and add more explosive rushes to the mix. The hope is that the addition of Lacy to healthy versions of Rawls and Prosise will propel the running back position to a more explosive 2017 as well. The offensive line plays a central role in all of this, but the offense has managed to be quite explosive with mediocre-to-bad lines during this stretch.

The pass defense is far more vexing. It feels like the personnel has just not been as good, and offenses have had a better plan of attack against the Seahawks zones. Seeing this decline puts an even finer point on how important it is that the Seahawks exited this strong cornerback draft class with fresh blood with high upsides.

Most people think of a suffocating defense when they think about the Seahawks. The oxygen levels have been increasing. Few people outside of Seattle think about the Seahawks as an explosive offense, but that is exactly what they have been during Wilson’s tenure. There are many paths to regaining their explosive advantage as a team. Not all of which require a return to their previous formula. One plausible scenario would involve the offense reaching new levels of dominance, lessening the burden on the defense. A more dominant run game can lead to fewer possessions for the opposing offense and less opportunity to create explosive plays.

It does not matter which path they choose to reverse this tepid performance in explosive plays on both sides of the ball. What matters is they succeed in reversing this trend if they have hopes of becoming a dominant team again.