There is a theory pervading certain segments of the Seahawks fan populace that: (a) Pete Carroll is holding Russell Wilson back due his run-centric offensive philosophy (b) Seattle’s best chance of contending after extending Wilson to a deal that could cost upwards of 18% of the team’s salary cap space is to install an offense that has Wilson pass more. The reasoning on that last part is the belief that you have to get more from a player who gobbles up that much of the cap to make up for the talent the team could no longer afford to surround him with. The logic makes sense superficially. While it is possible that putting Wilson in a more pass-centric offense could unlock some untapped potential, there is evidence that suggests he should uninstall the coaching Tinder app as Carroll may very well be Wilson’s ride or die pairing.

Quarterbacks are not created equal

Would you claim that Aaron Rodgers is the exact same player as Eli Manning? How about Tom Brady is the same as Deshaun Watson? Drew Brees and John Elway? It sounds ludicrous because it is. And yet, there are a lot of folks looking at advanced analytics that translate a statistical truth at the macro level to being equally applicable to every individual. Each player has unique strengths and weaknesses. What is good for Dak Prescott may not be good for Sam Darnold or Dan Marino. There are certainly some players who have gifts that allow them to play in a greater variety of ways. Others are more scheme-dependent. This is not limited to quarterbacks. Think about Bryon Maxwell, for example, and his performance in the Seahawks defense versus his performance elsewhere. The primary point here is that each player is different, with unique skills, and it is not at all safe to assume what is good for one will be good for another.

Why does that matter? Part of the underpinning of the movement to break up the Carroll and Wilson duo is an infatuation with the “modern offenses” that have players like Patrick Mahomes passing on 61.9% of neutral script situations. Reminder that neutral script is defined as first or second down, in the first three quarters of the game, and the score within 8 points (one score). Folks like Ben Baldwin and Nathan Ernst have helped me understand the value of looking at those situations when an offense really can call whatever they want as a better indicator of offensive approach. Everyone throws the ball when they are down in the fourth quarter by a lot, so better to screen out situations like that. The Rams and Jared Goff throw on 55.9% of neutral script situations this season. Seattle throws 40.3% of the time in those moments. Wilson is great, so just have him do what Mahomes and Goff do and the results will be the same. Or, so the logic goes.

The flaw there is a massive oversimplification that simply passing more often will achieve the same results. Not every quarterback is the same, and neither is every coach.

High volume passing is not the only way to win

The Chiefs and Rams get a lot of attention for scoring a ton of points and winning a lot of games this season. Part of their formula includes a heavy dose of passing. Although, it is worth calling out that the Chiefs passing on 61.9% of neutral script situations is significantly more than the Rams 55.9% passing rate. Kansas City is not alone in their extreme preference for the pass. Pittsburgh (61.7%), Cincinnati (61.0%), and Philadelphia (61.1%) also eclipse the 60% mark. If passing that much was the key to winning big, those teams should all be among the best in the league. The reality is that out of the four teams passing over 60% of the time in neutral script situations, only half of them have a winning record. That’s a small sample, so let’s broaden out and look at the relationship between neutral script passing rate and winning across the league this season.

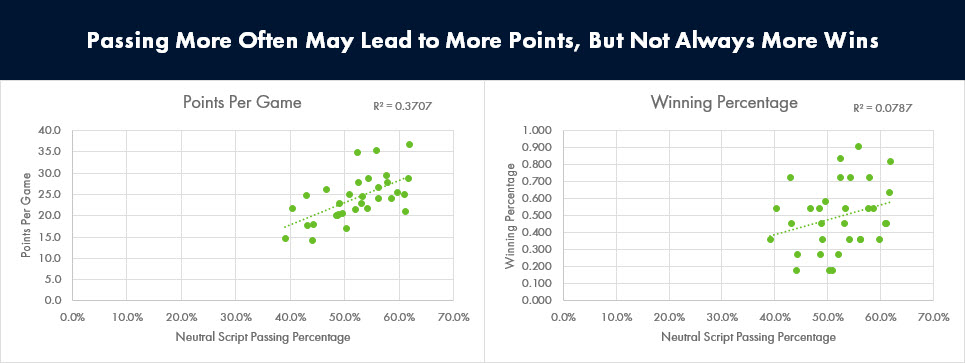

The way to read these charts is less about the trend line, and more about the clustering around the line. The R-squared number above is a numerical representation of how strong of a relationship there is between the x-axis and the y-axis. The closer to 1.0 the number, the stronger the relationship. There is a lot that goes into determining when an R-squared value is large enough to indicate a signal worthy of attention. What we can say is that there is a significantly stronger relationship between passing more often and scoring more points this season than between passing and winning. Even though the trend line has an upwards trajectory on the winning chart, the values are scattered far from it.

Of the 15 teams with a winning record this season, two of them pass more than 60% of the time in neutral script situations and five of them pass less than 50% of the time. If I were to try and spin it the other way, I would say 10 of the 15 teams with winning records pass more than 50% of the time in neutral script situations. The point to me is not whether a team should pass more or not. It is that there is more than one way to win.

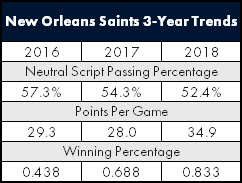

Take the New Orleans Saints. They are in the conversation for best team in the league and have one of the most potent offenses. They pass on just 52.4% of neutral script situations. What’s more interesting is they are bucking the “pass more” trend. Look at their last three seasons.

They have gone from passing 57.3% of the time in neutral script situations, to passing 52.4% of the time. They are scoring more points this season and winning a higher percentage of their games while passing less often. Should every team follow the Saints lead? Of course not. Only one team has Brees, Alvin Kamara and Mark Ingram. Only one team has Sean Payton. They are finding a formula that suits their personnel better, and one that is tougher for opponents to stop. Oh, and it is not requiring a new innovative young coach or quarterback.

Higher volume passing may lead to more points on average, but it is no panacea for creating winning teams, and it clearly not the only way to build a powerful, winning offense.

Wilson’s strengths align well with Carroll’s philosophy

I wrote a while back about Wilson’s greatest gifts and areas where he is mediocre. He is excellent as a play action passer. He is great under center. His deep throws are outstanding, and he avoids turnovers as well as anyone. He is also great when the game is on the line. Carroll is what I would call a point suppression coach. His philosophy is built around limiting the total amount of drives for both teams. More running plays eats up more clock. Taking away the deep passes and allowing shorter throws leads to more opponent plays to move down the field and more time off the clock. Fewer possessions means fewer total points, which increases the importance of turnovers as they provide one team with more opportunities than the other.

His offense values the ability to run effectively, and score off of play action passing, often deep down field. Limiting turnovers is key. Wilson is nearly a perfect fit, not only because of his passing ability, but because of his impact on the run game.

Wilson is one of the most efficient quarterbacks to ever play. As of now, he is one of only two players with a career passer rating over 100.0. The other is Aaron Rodgers. Wilson’s unique skill set, especially his ability to throw deep for big plays while rarely turning the ball over, makes him tough to beat in Carroll game.

Beyond that, Carroll’s games tend to be close. Seattle set an NFL record for consecutive games without losing by more than 10 points. That was not just about the legendary defense. They have not lost by more than a score this season, even with a suspect defensive unit. Wilson’s ability to rise to the occasion when the game is on the line lends itself perfectly to this Carroll trait.

Few quarterbacks will be more efficient, and better in clutch situations, than Wilson.

Run-centric offenses also suit Wilson

Wilson played for two schools in college, and played in some different styles of offense. Under Tom O’Brien at North Carolina State, Wilson was ranked 5th in the nation in pass attempts during his junior season. He transferred to Wisconsin for his senior season and played under the run-centric style of Bret Bielema. He ranked 66th in the nation in pass attempts that year. He was good in both situations, but he set the college football record for passing efficiency his senior season.

Part of what I fell in love with about Wilson coming out of college was watching him handle play action from under center in a pro-style system. That is not something every quarterback can do, especially in today’s game where many players are learning very limited and simplified shotgun offenses where their back is never to the defense.

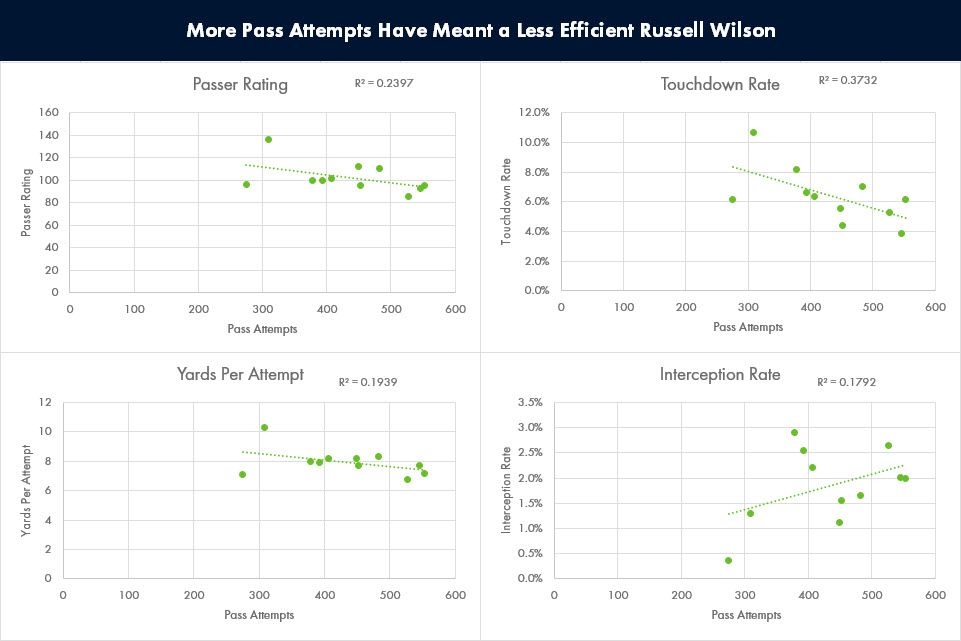

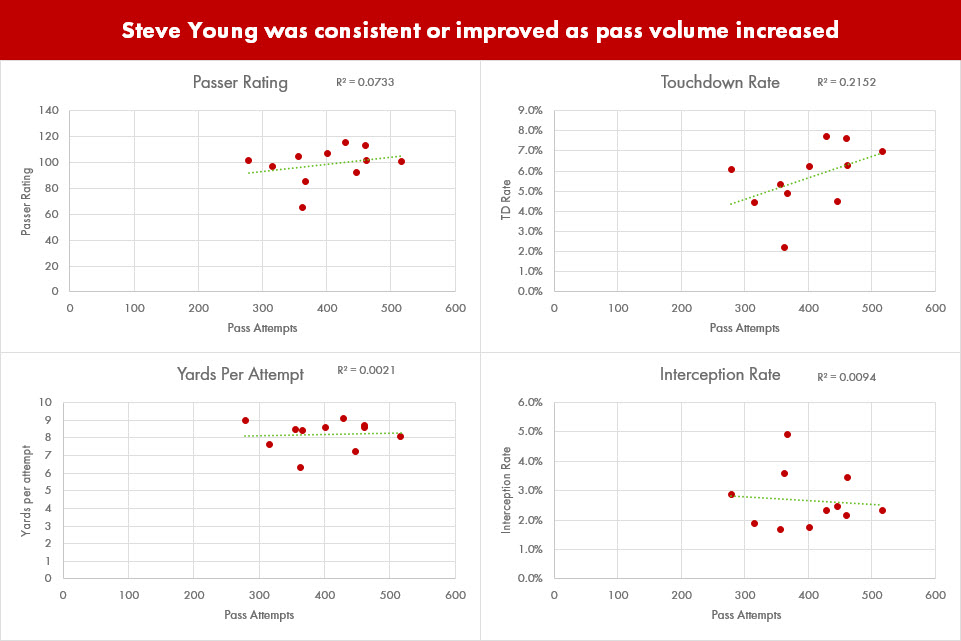

My observation of Wilson over the years is that he is at his best when the offense plays off of the run versus going heavy with the pass. I decided to look back over his career, including college, to see if there is any truth to that. In order to do that, I looked at the relationship between pass attempts and a few passing statistics.

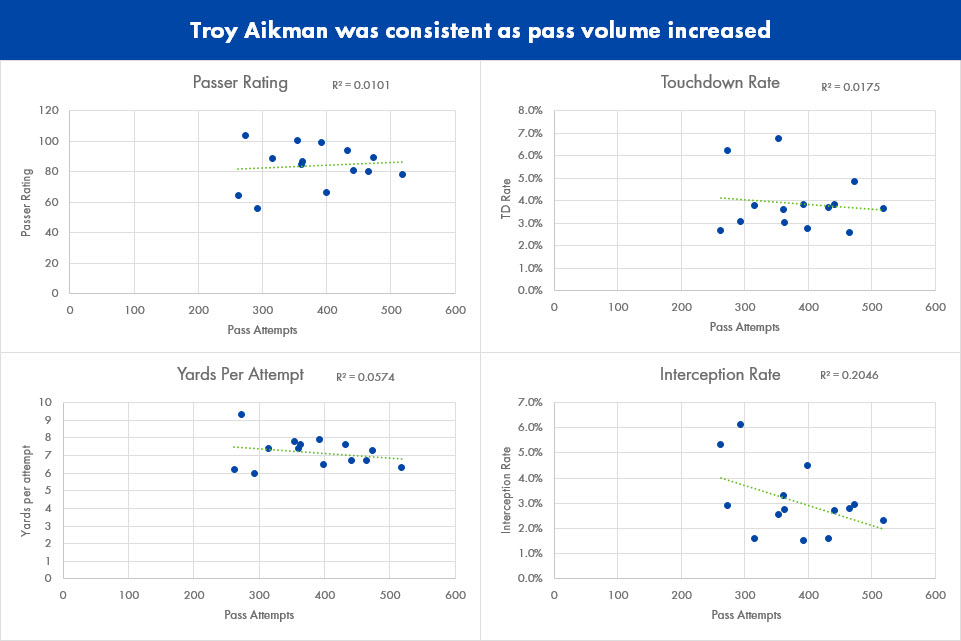

These charts include Wilson’s four college seasons as well as his pro seasons. College passer rating utilizes a different formula, so I calculated Wilson’s college numbers using the pro passer rating formula. That way, they are all on the same scale. None of these should be considered conclusive, but do provide some signal that Wilson’s passer rating, touchdown rate, and yards per attempt drop as he is asked to pass more, while his interception rate rises. I wanted to see if that was the case with every quarterback, so I took the time to compare with some other players.

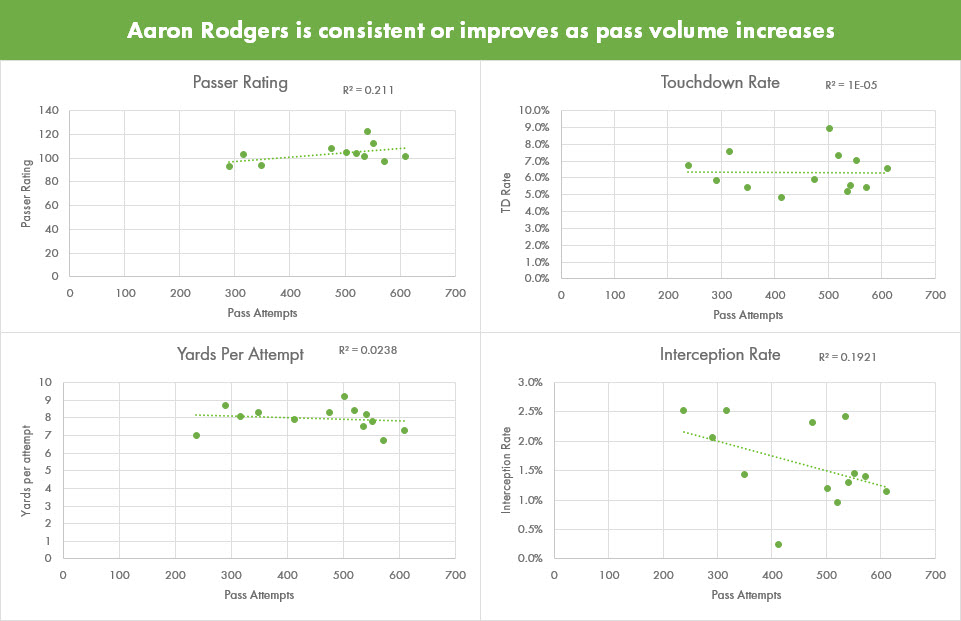

There is no shortage of other quarterbacks we could run these numbers for. My time, however, is in short supply so I stopped here. My conclusion from this data is not that Wilson is a lesser quarterback. I am certain that if I kept digging, I would find other great quarterbacks that had similar trajectories to Wilson. What this does indicate is that not all players lose efficiency as they pass more often. These numbers do not even prove that Wilson is less efficient when he passes more often. They do at least signal that may be the case, and so it should not be assumed that passing more often will result in a better Russell Wilson.

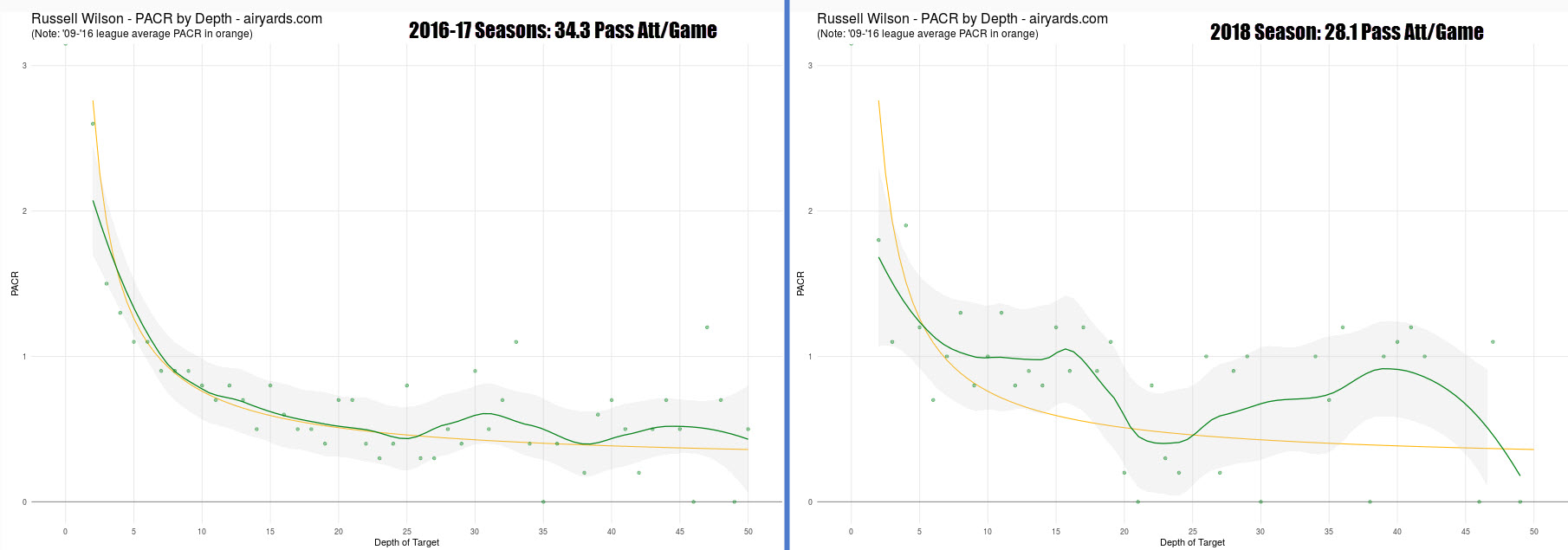

We can dig a little further by comparing Wilson’s efficiency on a variety of throws during seasons when he passed much more than he is passing right now. PACR is the most descriptive as well as the most predictive metric we have for quantifying QB passing efficiency, according to airyards.com. Take a look at how Wilson’s PACR compares to the league average in different seasons.

Wilson was basically a league average quarterback from an efficiency standpoint during the 2016-17 seasons when he set career highs for pass attempts. In this 2018 season where so many are claiming that Carroll and Brian Schottenheimer are holding Wilson back, he is having what is easily one of his most efficient seasons. His deep passing, in particular, is even more elite than usual.

Seattle has gone from throwing the ball 55.4% of the time in neutral script situations in 2016 and 53.9% in 2017 to passing only 40.3% of the time this season. Their scoring has gone from 22.1 points per game in 2016, to 22.9 last season, to 25.1 this season. Passing less often has certainly not hurt Wilson’s efficiency or the scoring offense.

Mike Solari does not explain the difference by himself

I am sure some who look at the Wilson comparison between 2016-17 and 2018 and immediately think, “Well, that’s because Tom Cable was coaching the offensive line and they were terrible at pass protection.” That would be a fine explanation if not for a few important points.

First, ESPN tracks pass blocking effectiveness specifically for offensive lineman, independent of quarterbacks who hold onto the ball or do other things that make their job difficult. They published an article this year that went into detail about how Wilson was one of the largest contributing factors to the pressure he was facing, and that the Seahawks line ranked 11th in the NFL last year in pass blocking while Cable was still around.

Second, Wilson has had some of his best seasons when Cable was still coach, including 2015 when he had his best stretch of passing over the second half of the season.

Third, even though the Seahawks currently rank 9th in ESPN’s pass block win rate for offensive linemen this season, they rank 29th in sacks per dropback. They ranked 20th last season under Cable.

Solari’s biggest contribution to the Seahawks offense and Wilson has not been his impact to the pass protection. It has been his impact to the rushing offense, which ranks first in the NFL, and has allowed Wilson to be at his most efficient self.

Be wary of trends and oversimplification

The Rams and Chiefs are amazing offensive teams. Other teams should absolutely be taking note of what they are doing that is working, and see what they might be able to incorporate into their offenses. There are also a lot of myths out there about these teams.

I just heard Rodney Harrison on the radio say that he would not hire an older offensive coach if he were running an NFL team because it is the new, younger guys who are changing the league. Really? Andy Reid and Sean Payton are not new or young and own two of the best three offenses in football. What unlocked their explosion this season is not an innovative new scheme. It is transformational talents like Mahomes, Kamara, Taysom Hill, Tyreek Hill, and Kareem Hunt. Similarly, Sean McVay is a wonderful and young offensive mind, but he is not new. He has been in the NFL since 2010, and was the offensive coordinator for the Redskins from 2014-2016.

Those Redskins offenses were good, ranking 10th and 12th in points scored. McVay did not produce a great offense until he had the oodles of talent the Rams boast on offense including Todd Gurley, one of the best offensive lines in football, one of the best receiving corps in football, and a #1 overall pick at quarterback.

There is not magic pill for being great. Elite talent makes teams great. Finding elite talent that other teams overlook or cannot accentuate is hard. There are some circumstances where a coach is actually an impediment to talent realizing it’s potential. Jeff Fisher with the Rams is a good example. Fisher never got to enjoy the elite offensive line and receiving corps that McVay enjoys, but he certainly was not getting the most out of Jared Goff or Gurley.

The Seattle situation feels much different. Carroll has not only already demonstrated that he can cultivate elite talent and win big, but I would argue he is getting more out of this roster than almost any other coach in the NFL could squeeze. Wilson is on pace for a career best in passer rating, touchdown rate, and passing touchdowns. He is right at his career best in interception rate (i.e., he is throwing fewer picks per throw) and yards per attempt. You saw the PACR numbers for this season above. What exactly is Carroll holding Wilson back from?

What makes a lot more sense is the Seahawks have taken a major step backwards in defensive talent. They have their franchise quarterback. They have the best running game in football. They have a much-improved kicking game on special teams. What needs the most help is a rebuilding defense. Carroll remains one of the best defensive minds in the history of the sport. Walking away from him on the off-chance that Wilson could be better if featured within a different offense seems incredibly risky, if not outright foolish. Not only is there evidence that Wilson would actually be less valuable in a high volume pass offense, but he would have to significantly increase the output of the offense to make up for what is almost certain to be disaster on defense. Ask Brees what it feels like to be an elite passing offense with no running game or defense.

Building a championship roster with a player making 18% of the salary cap, as Wilson is projected to earn in a couple of years, is incredibly difficult. Keeping Carroll or walking away from him does not change that. The Seahawks best chance to thread that needle is to stick with a coach who can maximize young talent on defense and extract optimal value from their more expensive player on offense. Carroll has shown the ability to do both. Walk away from that at your own risk, but realize getting that decision wrong could cost Seattle the prime of Wilson’s career.