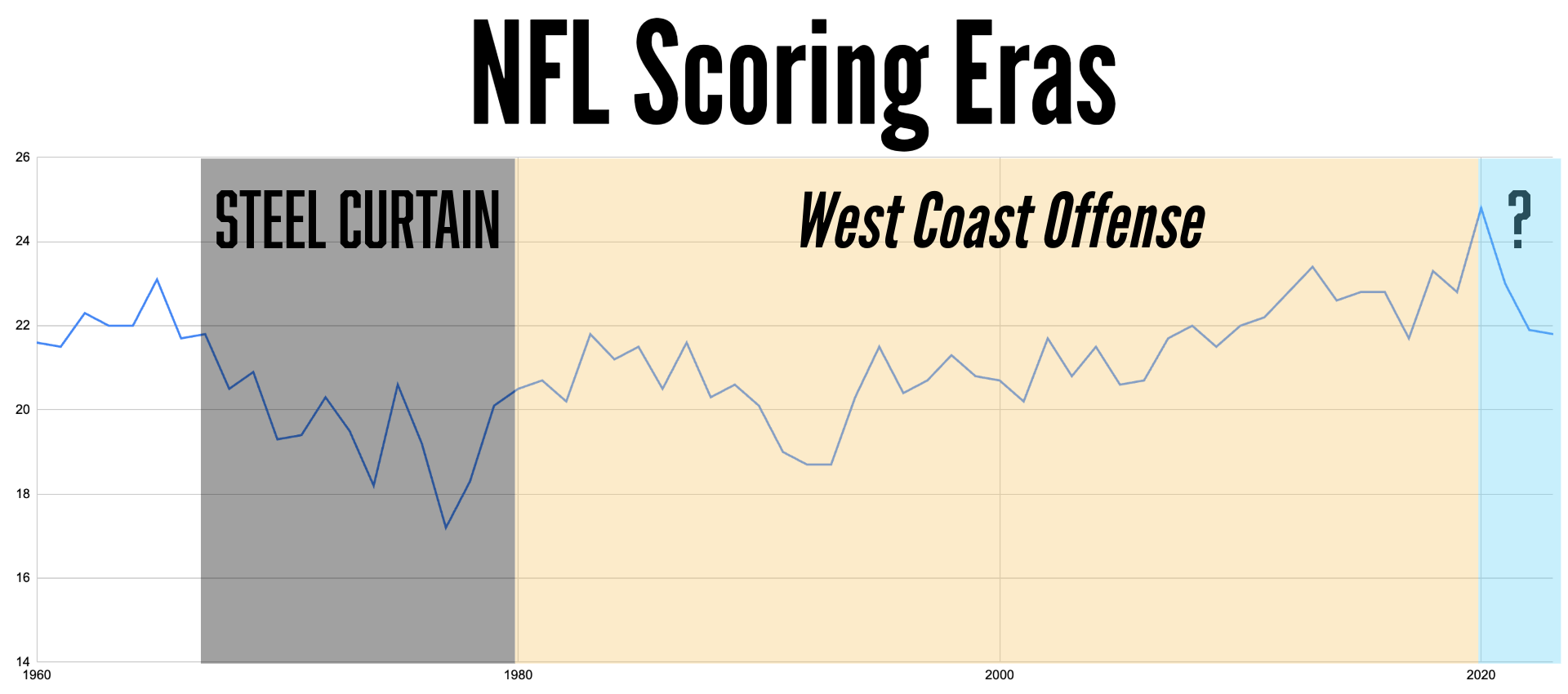

Tectonic movements can be subtle. The ground beneath our feet might move mere centimeters per year. The change goes unnoticed until those movements cause two plates to grind against each other, sending vibrations through the Earth. Football is a sport that invites that form of conflict each play between offense and defense. Different eras of football had more movement from one side of the ball than the other. The 70s were dominated by defense, with the emblematic Pittsburgh Steelers “Steel Curtain” defense leading the way to multiple Super Bowl wins. Bill Walsh almost single-handedly sent the league into an offensive era with the introduction of his West Coast Offense in the early 80s. Rule changes added wind to the offensive sails as scoring continued to climb after the turn of the century. There may be another tectonic shift underway. Scoring declined in each of the last three seasons for the first time since 1992. Schemes, tactics, and play callers are chipping away at the advantages offenses have enjoyed for decades.

The rise of the quarterback savants

Walsh’s impact on the game has been well chronicled. His introduction of higher percentage pass plays helped make passing a larger part of offenses. Pass attempts jumped roughly 19% from 26.2 in the 70s to 31.7 in the 80s. Completion rates across the league rose from 52% to 55% during the same time.

The increased reliance on passing put more responsibility on the shoulders of the quarterback. Joe Montana become the symbol of what it took to win consistently from the position. He and Walsh managed to not only bring about more reliable passes that replaced some running plays, but also found ways to make them explosive.

It took time, though, for the approach to spread across the league. Walsh’s coaching tree—with Mike Holmgren being arguably the most productive—methodically rose to power at a variety of NFL outposts and helped prove its efficacy by winning Super Bowls of their own in quarterback-centric systems.

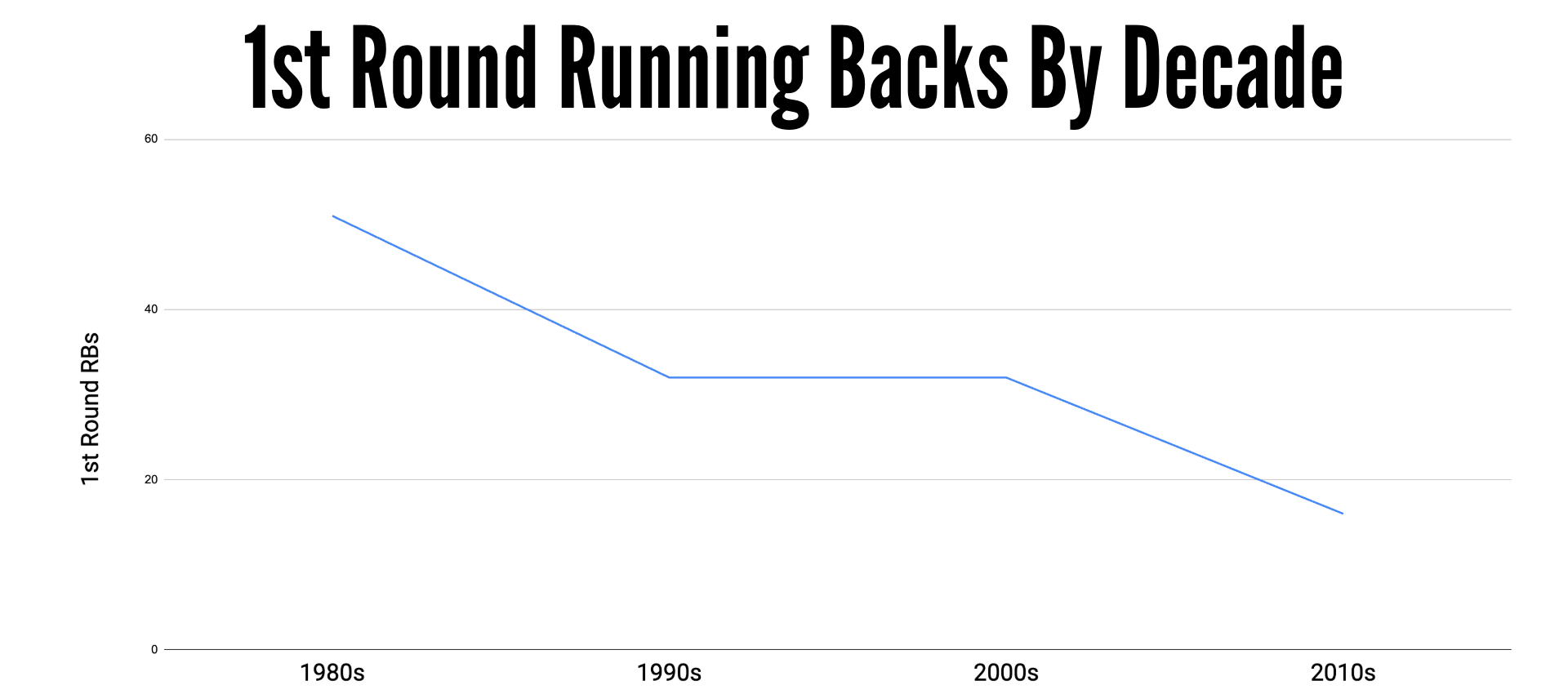

Running backs—from Roger Craig to Emmitt Smith—were still highly valued and utilized. Franchises did not hesitate to use their most valuable draft capital on the position. It took a decade for that philosophy of roster building to change. The expanding dominance of passing led to just 32 first round picks in the 90s being used on running backs, down 37% from the 51 selected in the previous decade. That number has halved to just 16 in the most recent full decade (2010-2019).

The shift to passing had another ripple effect. More kids grew up idolizing their favorite quarterback. General football camps were not enough anymore. Specialized quarterback camps became prevalent, with kids learning at early ages how to master the position.

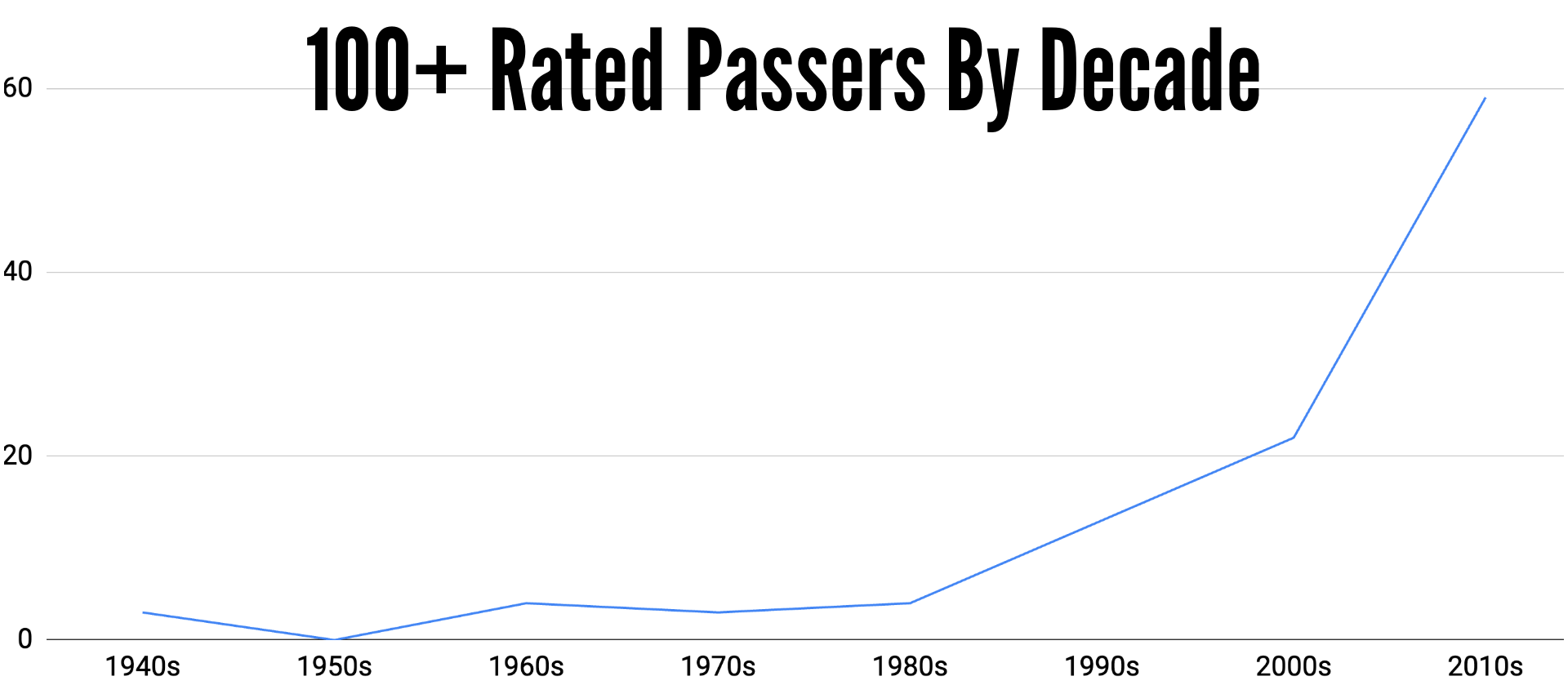

These savants first started entering the league in the late 90s, with Peyton Manning as the poster child. He was soon joined by Tom Brady and Drew Brees. This trio would dominate the new century of football. Each player had special physical gifts as a passer, but it was their cerebral approach to the position that helped them rise above the rest.

Defenses were not stagnant while offenses were evolving. They were devising ways to confuse quarterbacks by disguising pass rushes pre-snap that would cause lesser players to throw the ball exactly where the defense wanted or take a sack from a pass rusher they had not identified. Jim Johnson and his zone blitz scheme was among the most successful at preying on unsuspecting quarterbacks.

Manning, Brady, Brees, and Aaron Rodgers typified the savant quarterback who were able to win the chess match prior to the snap and know exactly where and when to attack the defense. This led to another massive leap in efficiency for players capable of making these reads.

Touchdown passes were increasing. Completion rates were rising. Passing attempts continued to grow. Interception rates dropped. All of the reward. Far less risk.

Increased access to data and analytics only added fuel to the passing fire. The idea of “establishing the run” became a meme. Teams that spent draft capital or early offensive downs (1st and 2nd) running the football were mocked by their fans.

Defenses mainly tried to combat this explosion with a more effective pass rush. Edge rushers were valued second only to quarterbacks. Dominant defensive tackles were right behind edge rushers.

The problem was that finding the next J.J. Watt, Von Miller, Aaron Donald, or Terrell Suggs was not easy, and even the best pass rushers still take a couple of seconds to reach the quarterback.

These savants became adept at getting rid of the ball before anyone could touch them. Brady became the greatest player of all-time in large part due to this ability. He had minimal mobility and made almost all his throws from the pocket. He had a knack for moving around within the pocket to buy an extra millisecond, but he and Manning would routinely get rid of the football in under 2.4 seconds. The average time to pressure in the NFL is 2.9 seconds, leaving Brady and Manning already thinking about the next play by the time most rushers would reach them.

That has left defensive play callers with a conundrum: how can they get these savants to hold onto the ball a half-second longer?

The swarm

Any farmer will tell you that insects can be among their greatest enemy. Locusts are possibly their greatest fear. Harsh conditions can cause locusts to congregate in close quarters and morph into a form that accelerates reproduction and leads to swarms that can devastate crops. NFL defenses have found themselves in harsh conditions for decades while offensive crops have thrived. The ability of these defenses to morph, and what they are morphing to, is putting them in better position to eat.

Pete Carroll’s Legion of Boom defense in the early 2010s took the league by storm with a simplistic single high safety look that relied on exceptional player talent at a variety of positions to suffocate offenses of all shapes and sizes. Even the savants struggled.

Manning never beat them, finishing 0-2, including a 43-8 thrashing in the Super Bowl. Brees started 1-3 before beating a weakened version in 2016 to finish 2-3. Rodgers started off 0-3 before winning his last two. Even Brady finished 1-2, with his only win coming when Carroll’s Seahawks made the most controversial decision in Super Bowl history at the 1-yard line. Combined, they were 5-10 against the best defense of that era, and one of the best of all-time.

That led to other franchises clamoring for the Carroll defensive scheme. They would find its success difficult to replicate. The simplicity of the approach made it easy for quarterbacks of all levels to diagnose what coverage they would be running. Multiple Hall of Fame players were required to make it work. Carroll, himself, was ultimately done in by an inability to find an answer once his elite players left the field.

What might have been a defensive-led dynasty in Seattle never materialized and the first two decades of the 21st century largely belonged to the savants, who would account for 10 of the 20 Super Bowl wins over that period.

Defenses continued to be tortured by descendants of Walsh and his offense. Sean McVay, Kyle Shanahan and Andy Reid brought their own variations to the league with sudden and sustained success. It became customary for their teams to enter games already knowing which linebacker or safety they would torment with schemes that would regularly force those players into a Sophie’s Choice of conflict between different route combinations.

Between their play calling and the evolved breed of quarterback capable of diagnosing defenses before the snap, it felt inevitable that scoring would only climb higher.

So why did the opposite happen?

Ted Nguyen of The Athletic wrote an excellent piece back in 2022 about the influence of Vic Fangio. In it, Nguyen goes into detail about the lengths Fangio would go to in his ornate schemes to confuse quarterbacks before the snap, and even after.

Fangio favored a two-deep safety system that specialized in limiting explosive passes. At the most basic level, a single-high safety defense, like Carroll’s, is going to invite deeper passes and rely on elite safety play to cover more ground. Two-deep looks make it tougher to pass down the field, but invite running plays as there are fewer defenders near the line of scrimmage. Fangio was willing to risk vulnerability against the run in order to minimize big plays through the air.

Nothing about that is revolutionary. Teams have been playing one deep or two deep safety looks for decades. What made Fangio’s approach more innovative was the lengths he went to disguise which coverage they were in prior to the snap, and the nuances of split field coverage principles after the snap.

In more simple terms: Fangio’s defenses were made to look like they were in one coverage before the snap, and then maintain the ambiguity after the snap so that quarterbacks were forced to process more of their decisions during live play.

Pre-snap, the defense is committed to showing the same Cover 4 shell for as long as possible so quarterbacks have to make reads after the snap. Even after the snap, it’s hard to draw a bead on what the coverage is because of how the defensive backs disperse from the top down.

Ted Nguyen, from Vic Fangio, the most influential DC in modern NFL

Quarterbacks are taught to read specific keys from a defense in order to diagnosis what they will be facing. For example, the weak safety is often a coverage indicator. Fangio knows this and puts that player in an ambiguous spot that keeps the quarterbacks guessing until sometime after the snap. It is not necessarily difficult to read a moment after the snap, but imagine doing that with Myles Garrett barreling toward you versus the comfy moments before the ball is snapped.

You can see how that can close the gap between the time to throw and the time to pressure. Every extra tenth of a second of diagnosis post-snap increases the odds of pressure getting home or a hurried decision that ends poorly.

This approach replicated through the league, but there was another step forward in the works from another defensive wizard. Mike Macdonald had studied all these defensive masters, with a heavy emphasis on pressure packages that had been effective in stopping 3rd down plays.

Macdonald drew inspiration from zone blitz legends, Jim Johnson and Rex Ryan, while finding ways to limit the need for extra rushers. His contribution has come in two main ways:

- First, he makes diagnosing where the pressure is coming from difficult while generally only sending four rushers after the quarterback

- Second, he has devised a way to teach his players a wide variety of positions, responsibilities, and pressure patterns that allows him to mix fronts and coverages from game-to-game, and often from play-to-play

Nguyen wrote about Macdonald as well after he was hired as the Seahawks new head coach. In the story, Nguyen explains what makes Macdonald’s pressure packages unique.

When he does blitz, offenses usually have no idea where the pressure is coming from because his defenses can present so many different looks from week to week. The Ravens were so multiple because of the unique way Macdonald teaches and structures his pressure packages.

– Nguyen

Macdonald’s success at University of Michigan and Baltimore not only helped him land a head coaching gig, but has already started the branches of his coaching tree to grow with defensive coordinators from his staff occupying spots in places like Tennessee and Miami.

The combination of Fangio’s coverage disguises with Macdonald’s pressure disguises has done something more than raise the bar for opposing signal callers. It has changed expectations for what can realistically be elicited prior to the snap. If any player can have any coverage or pressure responsibility, and there is not a reliable way to pick out who is going to do what, quarterbacks are increasingly being asked to read defenses after the snap. Not everyone is capable of that feat.

Macdonald pushes things further by regularly rotating his players so that it even becomes hard to pick out a specific player an offense wants to pick on. They either won’t be in the game or in the same position or the quarterback will just have too much other pre-snap homework to finish before identifying the weak link defender.

The effect? Quarterbacks combined to average 188.3 passing yards in Week 1 of the 2024 NFL season. That was the lowest total for any week in 17 years.

Cody Alexander, of MatchQuarters.com, specializes in researching and dissecting defense.

“The ‘new’ Ravens system crew is probably the most diverse regarding pressure use and coverage,” Alexander said. “That includes the Seahawks, Chargers, Titans, Ravens, and Dolphins. Multiple hybrid schemes and fluidity within those packages are a hallmark of that system. Interchangeable parts allow them to run a volume of calls. This is confusing for the offense but simple to execute for the defense.”

Alexander sees these defenses as having an advantage over even some of the Fangio schemes.

“Fangio-adjacent systems are also well versed in the coverage aspects but tend to struggle against the run because there is a lot of pressure to win matchups up front that the safeties must tackle,” Alexander said.

What comes next

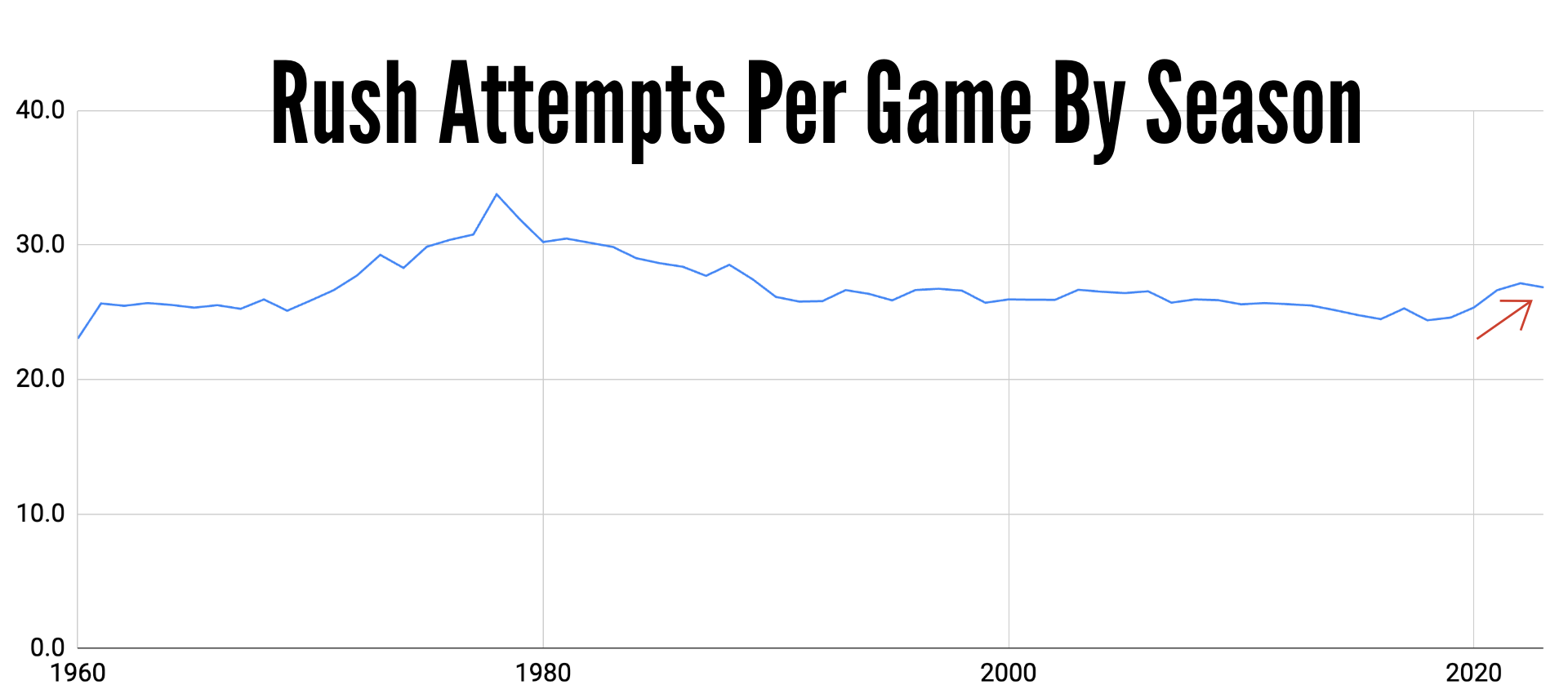

Defenses that play more two high safeties, even if it starts disguised as something else, remain susceptible to offenses who can run the ball well. There are some ways defenses can mitigate that risk, but it remains a vulnerability.

We are seeing some signs that offenses are investing more in their run game. Interior offensive linemen have seen their contract values soar. Running backs are seeing a mini revival in value. Christian McCaffrey won Offensive Player of the Year in 2023. Saquan Barkley signed a big free agent deal with Eagles, with Josh Jacobs and Jonathan Taylor also inking big contracts. The 2023 draft had a top ten pick spent on a running back for the first time since 2018 and two backs selected in the first round overall.

Rush attempts per game rose four straight seasons from 2018 to 2022. That was the first time that has happened since 1978. The increase was modest at just over 11%, but the trend has been steady and coincides with the defensive changes.

Quarterbacks who can marry off-script ingenuity with on-script execution become the unicorn every team seeks. There will be more post-snap surprises that require elite instincts in the moment instead of the more robotic pre-snap diagnose and attack. Players like Patrick Mahomes and Josh Allen would thrive in any era, but their ability to improvise takes on even higher value in this new NFL. Allen’s ability to create with his legs adds another dimension.

There are more pre-snap savvy quarterbacks in the NFL than ever. They may not be to the level of the savants, but they grew up learning how to read keys and attack weaknesses in the defense. These coverage and pressure-bending defenses, though, have helped to create a deep middle class at the position who have no advantage over one another.

Offenses are not standing still. Coaches like McVay, Shanahan, and Reid continue to tinker in their labs. McVay was one of those coaches who invested a lot in the interior offensive line and had changed their run schemes to involve more power to take advantage of the lighter defensive personnel and lighter boxes. Shanahan has enough versatility on offense to attack defenses in a variety of ways that helped him lead his team to a Super Bowl appearance.

That game will largely be remembered as Patrick Mahomes growing his legend as the best player in the game, but it was Steve Spagnuolo’s defense holding the 49ers offense to 19 points in regulation and 3-12 on 3rd downs that made the victory possible. His defense finished 2nd in the NFL in points and yards allowed, while Mahomes and the offense struggled through a middling season.

Quarterbacks will continue to get the glory, but defenses are forcing them to evolve once again. The teams best able to hide their intentions in coverage and in pass rush will have an advantage that should be more durable than earlier scheme trends. The ground has shifted. Innovators like Macdonald may be ready to cause a full blown quake.